Porter’s Value Chain is a strategic tool that helps you map out the internal activities you perform that add value for your customers.

When a chef cooks a meal, they can sell that meal for more than the cost of the raw ingredients. Why? Because by cooking the meal, the chef created something more valuable than the ingredients alone.

Using business language, we can say that the chef has added value. A critical factor in all restaurants’ success is to maximize the price difference between the sales price of their output (their food) and the cost incurred creating that output (ingredients plus the cost of the chef plus other overheads).

Porter’s Value Chain Analysis

The example of a restaurant may seem very simple, but all businesses, no matter how complex, must behave in a similar way. They must take a bunch of inputs and produce an output.

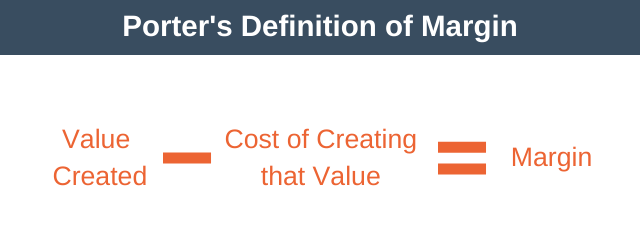

The gap between the value you create and the cost of creating that value is known as your margin.

And if you understand margin, you can define the Value Chain as being the set of all activities an organization performs to create margin or create value for its customers.

Why Create a Value Chain?

The purpose of a value chain is to help you understand the activities within your business that create value for your customer.

Once you understand this, you can then invest more in your value creation areas and eliminate unnecessary business activities. Doing this will improve your competitive advantage and speed up your production, ultimately increasing your profit margins.

The Value Chain was developed by Michael Porter, a Harvard Business School professor. Porter describes the Value Chain in detail in his 1985 book, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Advantage.

Components of Porter’s Value Chain

Porter’s Value Chain isn’t based on examining accounting costs and departmental budgets. Instead, it takes a process view of how an organization transforms inputs into outputs step by step, which customers then purchase to generate margin.

With this approach, Porter was able to design a generic chain of activities (or generic Value Chain) common to all businesses.

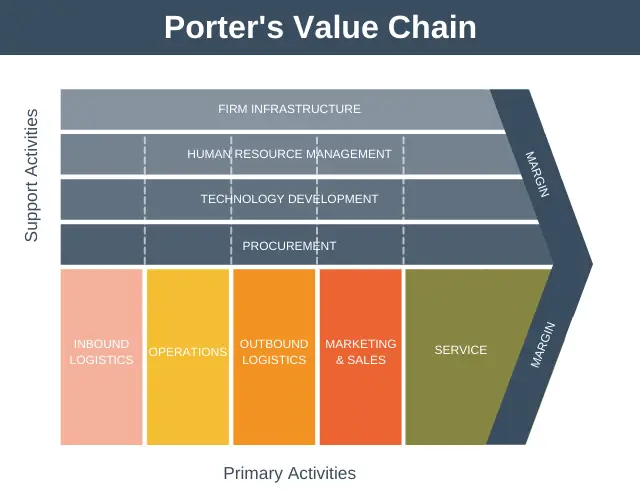

Broadly speaking, we can say that this diagram is broken down into two categories:

- Primary Activities: that directly develop your inputs into outputs. Note that these primary activities are drawn in the order they happen; for example, inbound logistics happen before outbound logistics.

- Support Activities: that help your primary activities run more smoothly.

Let’s take a deeper look at both of these categories.

1. Primary Activities

Each of your primary activities will directly relate to the creation of your product or service. These are the activities that build value and competitive advantage.

Inbound Logistics

Inbound logistics is the process of orchestrating the receipt of inputs and then storing and distributing them internally. Managing your relationships with suppliers is a crucial part of this activity.

Operations

Once inbound logistics has moved the goods to the right location, operations turn your inputs into outputs.

Outbound Logistics

Outbound logistics deliver your product to your customer once operations have produced it. For physical products, this may mean that you dispatch the product immediately or store it for a period.

Marketing & Sales

Just because you have created a product doesn’t mean that your market knows about it or wants to buy it. Marketing & sales are responsible for ensuring the market knows about your product and wants to buy it instead of your competitor’s product.

There are numerous sub-activities involved in this step, including advertising, setting prices, channel selection, partnerships, and managing your sales pipeline.

Service

Service activities are those that occur after you have made the sale. Their purpose is to maintain or grow your product or service’s value after you have sold it.

Subactivities that occur in this step include customer service, activities to reduce churn, customer training, and activities to maintain or grow engagement.

2. Support Activities

The support activities support your primary activities. The dotted lines in the diagram show that support activities can help a specific primary activity and play a role across all primary activities. For example, Human Resource Management supports marketing & sales but could also support logistics.

Procurement

Procurement is the process of purchasing the inputs you need. Procurement, also known as purchasing, involves finding new suppliers and negotiating the best price.

Human Resource Management

Human resource management plays a crucial role in supporting the other areas of the business. This activity involves hiring, training, rewarding, employee wellbeing, and retaining good employees.

In the knowledge economy, finding and retaining talented employees can be a significant source of competitive advantage, which is why many companies even have talent management departments.

Technological Development

Technological development refers to any technology needed to support turning your inputs into outputs. Technological development includes software, hardware, infrastructure, or procedures used to create your outputs. It also includes your R&D (research and development) department.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure is a catch-all activity for functions that support the entire value chain.

Note that Infrastructure is the only support activity in the diagram that doesn’t have dotted lines going through it. That is to indicate that it truly supports all primary activities equally.

Subactivities of infrastructure include general management, finance, and the legal team.

Using Porter’s Value Chain

Now that we’ve covered the basics of the Value Chain, the first thing to realize is that support activities are just as important as primary activities; they just provide a different type of advantage.

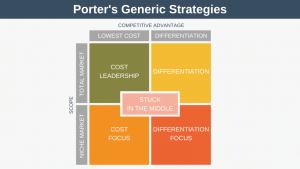

Primary activities are the source of cost advantage, whereas support activities (such as general management and R&D) are the source of differentiation advantage.

Using Porter’s Value Chain isn’t quick or easy and will require a lot of deep thought. In the first instance, the Value Chain can help you obtain a clear picture of how your organization generates value. To get this picture, you can follow these steps:

1. Map Out Subactivities

For all primary and support activities, write down the processes or activities that create value.

Each organization is unique, so no two value chains should look the same. Once you’ve completed this step, you’ll have a value chain diagram showing the essential value-creating parts of your business.

2. Analyze the Subactivities

The next step is to analyze all the activities you’ve written in your diagram and think about whether each activity carried out provides more value to your customer than it costs.

If you find areas where you can’t definitively say that, yes, these activities provide more value than their cost, then you should consider changing or discontinuing these activities.

By performing this step regularly and making adjustments, you will continually grow your margin and the value you provide to your customers.

3. Examine The Linkages

The Value Chain of an organization isn’t just a collection of independent activities. It’s actually a collection of interdependent activities related by linkages.

A change within one activity will impact other activities. For example:

- You identify a link between recruiting and sales so that the better the salespeople you hire, the more products you sell.

- You identify that an interactive chat system on your website (Technological Development) can result in increased sales (Marketing & Sales) and better post-sales customer care (Service).

Because linkages are so important, coordination and communication between activities are as important as the activities themselves. This means that optimizing your links is as important as optimizing your activities to create a competitive advantage.

Other Uses

The Value Chain is a powerful strategic tool, and you can use it for more than just creating a shared view as to how your organization generates value, including:

1. Create a Target Operating Model (TOM)

You can use the Value Chain to design how and where you’d like to add value to your chain.

You might not be there yet, but your target operating model can act as a blueprint of where you want your destination to be.

For example, consider a car manufacturer such as Volkswagen moving towards fully electric cars and having a target operating model that supports this.

A Gap Analysis can be an excellent tool to use to plan how to move step-by-step from your current operating model to your target operating model.

2. Ensure complete coverage in major change initiatives

Suppose you’re planning a significant change program. In that case, your Value Chain can act as a useful checklist to ensure you’ve considered the implications for all activities and all links between them within your organization.

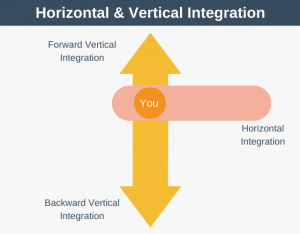

3. Understanding acquisition fit

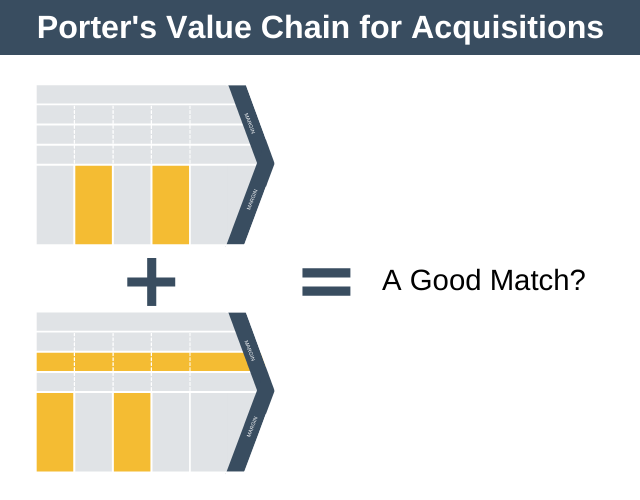

Suppose you’re considering the acquisition of another organization. In that case, comparing your Value Chain against that of the organization you’re acquiring can help you determine if the investment is a good fit or not.

In this example, you can see that the drivers of value creation happen within different activities. It’s up to you to decide if that makes the target organization an ideal target or a poor target.

Value Chain Example

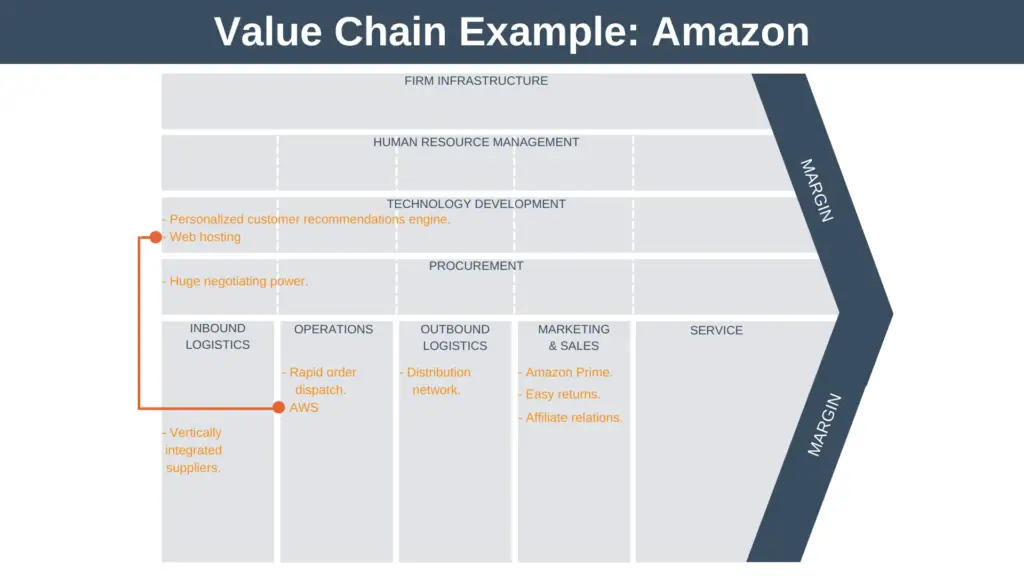

For this Value Chain example, we’re going to take a look at Amazon.

Amazon is a large and complex company, so we’re only going to scratch the surface and map out some of its most important subactivities in this Value Chain example, which you can see below.

In this example, the value-adding activities Amazon performs are written in orange text. Additionally, you can see that we’ve linked two activities together, web hosting and AWS.

If you don’t already know, AWS (Amazon Web Services) is a fully-featured cloud platform provided by 200 data centers globally. It allows organizations to, amongst other things, host and serve their website at scale, only paying for what they use.

What’s interesting is that before creating AWS, Amazon had already been hosting its own website at scale for years. The creation of AWS took this core competency and offered it as a service in its own right. Mapping your Value Chain allows you to see linkages that already exist, but it also allows you to think of new linkages.

It’s impossible to say if Amazon used a Value Chain to spot this opportunity, but hopefully, from this example, you can see the power of understanding your key value-creating activities and the links between them.

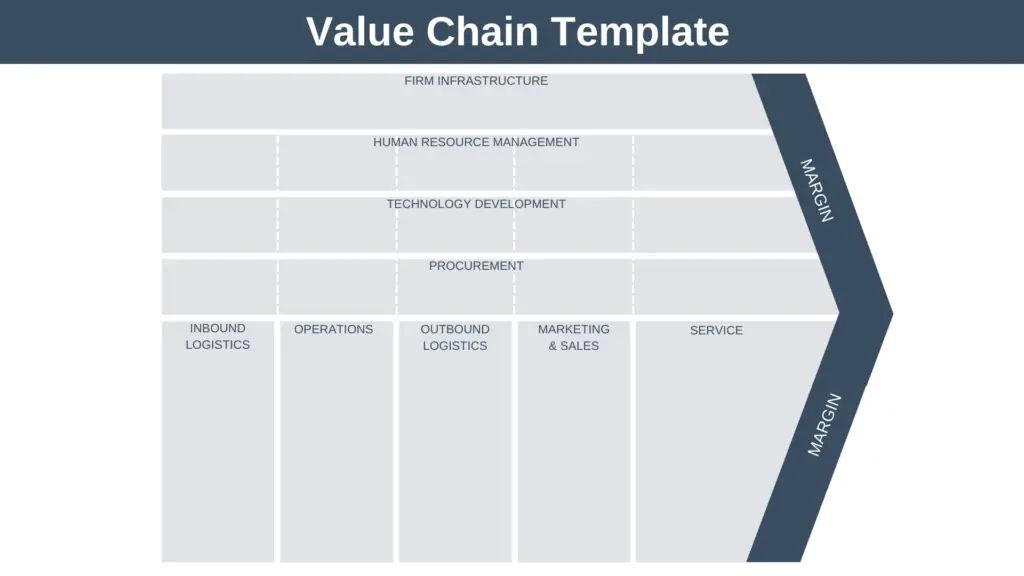

Value Chain Template

If you would like to perform your own Value Chain analysis, we’ve provided a Value Chain template you can download here.

Advantages and Disadvantages

There are several advantages and disadvantages associated with the Value Chain.

Advantages

- The key advantage of Porter’s Value Chain is that it allows you to increase your margin. It does this by clarifying how you create cost advantage and separately differentiation advantage. From this, you can cut costs or increase investment to boost your margin.

- It allows you to create a shared understanding of how value is created within an organization.

- You can use it in many different ways.

Disadvantages

- Once you have created your Value Chain, you need to keep revisiting it to keep up with changes within your organization.

- The model is focused on your internal environment and doesn’t consider external factors such as competitors, industry trends, consumer trends, etc.

- By focusing on the detail of activities and how they interact, you can lose sight of the broader strategic picture.

Value Chain Summary

Porter’s Value Chain is a tool enabling organizations to understand the key activities they perform that create margin.

Understanding how you create your margin is the first step to boosting your margin.

By analyzing the five primary activities and identifying efficiencies, you can increase your cost advantage. By analyzing support activities and identifying efficiencies, you can improve your differentiation advantage.