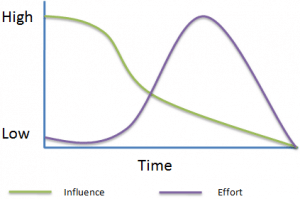

The traditional approach to project management planning and risk is to create the plan and then analyse it for risks. We would then manage those risks accordance with our Risk Management Process. In this article we’re going to consider embedding risk thinking into the act of planning itself.

This is different from traditional thinking because we’re not saying you need to trade off scope, time, or budget against each other in order to maximize your chances of a successful project. What we’re saying is that you should structure your project so that it has the maximum chance of being successful even if the scope creeps, your time is reduced, or your budget is cut halfway through the project.

In doing this we are loading the dice in our favour, making it far more likely that the project will be a success, no matter what happens along the way. Let’s look at a couple of examples to crystallize the idea. The first example is from an article which appeared in Information Week in 2001.

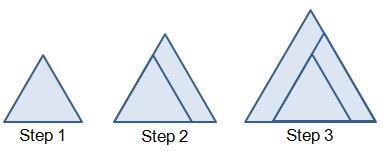

Example: Two Ways to Build a Pyramid

Pyramids were built as tombs for pharaohs. This means that we have the requirement that the pyramid be finished at the point when the pharaoh dies. A classic way to build a pyramid (and most intuitive) is to start by building a strong base or foundation upon which we can build up the pyramid in layers.

There is an obvious problem with this approach. We want to build the pyramid to be as large as possible but we must have it complete by the time the pharaoh dies. This makes it difficult to know how big we should make the base as we don’t know when the pharaoh will die. Because of this we might decide to make the base large if the pharaoh is young and smaller if the pharaoh is older. This seems sensible but you can probably see that there is still an intrinsic risk in this approach – what happens if the pharaoh dies at a much younger age than we expect?

In this case we would be left with an unfinished pyramid to put him in. Not good. If the pyramid wasn’t too far away from completion when he died then we might rush to finish the pyramid, working 24 hours per day and getting in extra workers. You can think of this as being analogous to rushing in death march fashion to complete your project as the deadline approaches.

There is another way we can choose to build our pyramid. We can plan to build it in a certain way so that the pyramid is ready whenever the pharaoh dies, whether he dies unexpectedly in his prime or lives to a ripe old age. The method would still work even if some unforeseen war or plague was to wipe out half the workforce. In effect we are structuring our project for success. The approach is shown below:

Using this approach the pyramid is ready on time even if scope, available time, or budget decrease. It is also a suitably large pyramid if the pharoah lives to a ripe old age. If the pharoah was to die at any stage during construction then we’d simply have a small rush (as opposed to a massive panic) to complete the section currently under construction. Let’s look at another example more closely related to project management as we know it today.

Example: Building an Internet Service

In this example we’re required to build a large scale Internet service and we’ve been given six months to do it. The logical approach to this might well be to first design the architecture and the core services of the platform, and then build the user experience on top of this. Let’s (simplistically) say we had planned for the architecture and core services work to take three months, leaving three months to complete the user experience.

For the purposes of the example, let’s assume that the architecture and core services actually take 5 months to build. Then what? Well, we’re going to going to have a mad rush to finish the user experience for a start. We’re also going to have wasted investment, as we will have designed an architecture and built core services that we won’t be able to use. In effect, we have made the same mistake as the first pyramid builder by assuming that we need to start with a solid base or strong foundation in order to build our service.

Perhaps a better approach would be to copy the approach of the second pyramid builder. We would build a vertical slice of functionality, perhaps the “login” feature and get it right. We would then build the next vertical slice. In this way there is never any danger of wasted investment. Additionally, short feedback loops keep the project moving in the right direction.

Another alternative to the same problem might be to build the user experience with the core services just “faking it”. After this we would begin to develop the core services so the platform would scale. If our timeline was cut unexpectedly, then with our complete user experience but only moderately developed core services, perhaps we could go to market as a trail rather than a fully blown scaled solution, whilst we continued to work to scale the platform after the initial release.

Summary

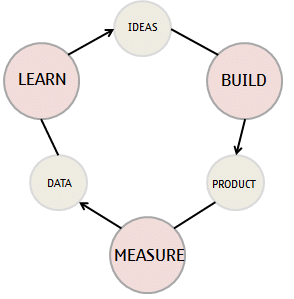

The approaches described above to planning and risk is counter intuitive, but demonstrate how thinking about risks to determine the shape of the plan can hugely derisk your project, making it much more likely to be a success. The approaches described above where we frequently build a small part of the overall, but we do it quickly and to completeness, have much in common with the Agile software development process, but here we are applying it to larger projects or programs.

I hope you can clearly see the benefits of embedding risk management into the planning process itself, rather than it just being something which is performed after or as an aside to project planning.