The ladder of inference is a tool that can help you avoid your biases and beliefs, enabling you to make better decisions. It can be particularly useful to stop yourself from making rash decisions.

Imagine you are the owner of a small e-commerce company. You hire a freelance web developer, Mike, to build you a new website, which you want to launch on January 1st, in the hope of skyrocketing your sales over the next year.

The deadline to launch your new site is getting close, and Mike has failed to respond to an email you’ve sent within 24 hours for the third time in a row. You have to call Mike each time this happens to follow up.

You’re frustrated with Mike’s repeated failure to respond to your emails. You’re worried you’ll miss your deadline, and your big plans to boost sales next year will be immediately behind schedule.

You decide that you will have some strong words with Mike about the importance of professionalism. If that doesn’t get him to perform better, you’re going to fire him and find someone who understands the importance of responding promptly and being professional.

Doing this seems perfectly reasonable to you as a frustrated business owner, but what if you had avoided jumping immediately to “action” and instead taken the time to uncover more facts?

In that case, you’d have discovered that Mike is having email problems, and your emails are being inexplicably and automatically moved to his spam folder. Mike is a one-person business and is stressed because his email is playing up while he’s working hard to try and launch your website on time.

Would you still choose to read the riot act to Mike if you knew this? Probably not.

If this example is familiar to you, and you’ve been annoyed with someone’s behavior only to realize later there were extenuating circumstances, then you’re guilty of climbing the “ladder of inference.”

The ladder of inference is a framework that can help you avoid making this kind of mistake. It’s particularly useful to stop yourself from making rash decisions or when making more significant decisions, such as setting your business strategy or even buying a house.

In this article, we’ll explain the model, show you how to use it, and look at an example so that you can make better-informed decisions in the future.

What Is The Ladder of Inference?

The ladder of inference, sometimes called the “process of abstraction,” was developed by Chris Argyris, a business theorist. It’s a tool that can help you understand how you think and make decisions, and understanding how you think can help you to make better decisions.

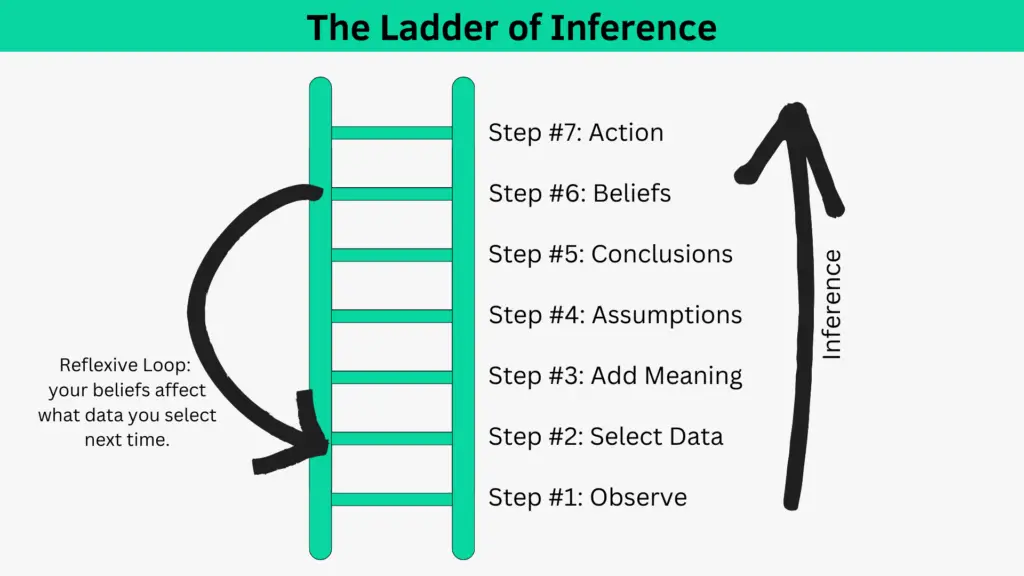

You can think of the ladder of inference as a ladder made up of seven rungs. For every action you take, you progress through all seven rungs, usually without realizing it.

At the top of the ladder are the actions you take. You take these actions based on all other ladder rungs, starting with the lowest rung, “Observe.”

Each of us performs these steps almost instantly, without realizing it, multiple times per day.

Let’s walk through what happens on each step of the ladder. We’ll do this quickly and then look at an example to bring the ladder to life.

Step #1: Observe

You observe the world around you, which is the reality and facts of a situation.

Step #2: Select Data

You filter out the data you think is irrelevant to your situation. You cherry-pick what’s important based on your beliefs and experience.

Step #3: Add Meaning

You interpret your selected data by adding meaning to it.

Step #4: Assumptions

Now that you’ve added meaning, you can make assumptions or apply your previous assumptions or beliefs.

Step 5: Conclusions

You can now draw conclusions about what the situation means by combining your facts, meaning, and assumptions.

Step 6: Beliefs

Based on the conclusions you draw, you begin to form beliefs. You carry this embryo of a belief into future situations, and each time you draw a new conclusion using this belief, you reinforce it.

In this way, you create a negative cycle, called a reflexive loop, whereby you make decisions based on your beliefs, and each decision you make reinforces your beliefs.

Step 7: Action

Finally, based on the culmination of all the previous steps, you take what you believe to be the right course of action for you.

Unfortunately, you often act based on your beliefs and assumptions rather than seeking out and considering all the facts. Ultimately, this results in you choosing the wrong course of action.

Ladder of Inference Example

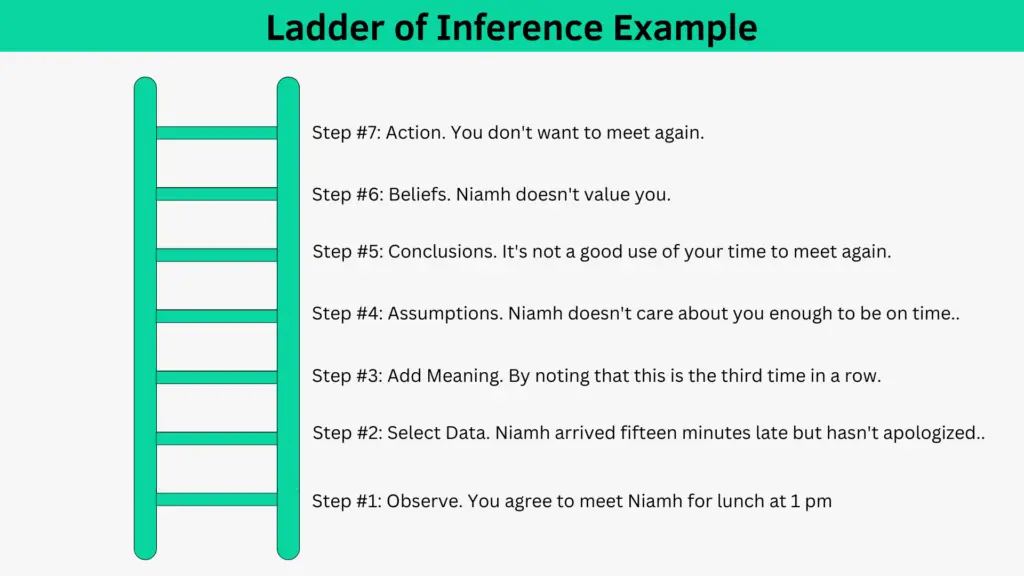

In this example, imagine that you’re meeting your friend, Niamh, for lunch. Here is how you move up the ladder in this example.

- You agree to meet Niamh for lunch at 1 pm (“observation”).

- Your “selected the data” is that Niamh has arrived fifteen minutes late but hasn’t apologized.

- You “add meaning” by noting that this is the third time in a row that Niamh has arrived late for lunch.

- You “assume” that Niamh doesn’t care about you enough to bother being on time. This is “an assumption” because you don’t actually know what Niamh thinks about you.

- You “conclude” that it’s not a good use of your time to meet Niamh again because she doesn’t value your friendship.

- Your conclusion that Niamh doesn’t value you becomes a “belief.”

- Finally, towards the end of lunch, when Niamh asks when you’d like to meet for lunch again, you take “action” by informing her that you’re really busy at the moment, so you don’t think it’s a good idea, right now. Here, you’ve taken the best “action” for you based on all the previous steps of your ladder of inference.

At the end of lunch, you’re not going to meet Niamh again, and Niamh doesn’t know why.

You’ve climbed the ladder of inference and probably haven’t even realized it. Because the truth is that there could be any number of reasons why Niamh was late meeting you for lunch.

Deep-Rooted Ladder of Inference Example

This time, let’s look at a more deep-rooted example of the ladder of inference. Imagine that you work in an office environment, and your boss offers you a chance for promotion.

- Your boss offers you a new job as “Head of Statistics” (“observation”).

- You “select data” by worrying about the word statistics in the job title because you’ve never been good at math.

- You “add meaning” by thinking your bad math could set you up for failure and humiliation.

- You “assume” you’ve been able to hide your poor math until now, but this new job will completely expose you.

- You “conclude” you’re not going to take the job.

- Your conclusion reinforces your “belief” that you’re bad at math.

- You take “action” by telling your boss you don’t want the job.

Deep-rooted negative beliefs such as “I’m bad at math” can span all the way back to childhood, be very difficult to spot, and take a lot of work to rectify.

These beliefs can come about for any reason. Maybe all it took was a teacher or parent flippantly saying that you’re not good at math to ingrain the beginning of the belief. After that, you spend the rest of your life making decisions based on your belief you’re not good at math. For example, maybe you choose to study humanities at university rather than a STEM subject because of this belief.

But are you actually bad at math? Maybe you just formed a flawed belief early on and have never taken steps to test out that belief. Perhaps, with some hard work, you could learn to enjoy math.

If you like to learn more about overcoming negative beliefs, then we have an article explaining how to overcome negative beliefs

How to Avoid Climbing The Ladder of Inference?

There are three simple steps you can take to stop yourself from climbing the ladder of inference:

- Reflect: take time to reflect on the soundness of your logic before making decisions. Do this from a position of understanding that your reasoning may be flawed because you’re missing some facts.

- Share: take the time to share with others the decision you’re about to make and the logic behind it. Doing this will trigger a conversation and allow others to provide input you may not have been previously aware of.

- Ask: take the time to ask others what they are thinking.

Let’s return to our original example, where you’d ended lunch without agreeing to meet Niamh again.

How could you have used the techniques above to reach a better decision?

Well, you could have asked Niamh any one of these questions to find out what she was thinking:

- “You’re a little late. Is this a bad time for you generally?”

- “Did you have any problems getting here today?

- “You know, if it’s a struggle for you to get here, I’m totally fine if you’d prefer to cancel next time.”

Any of these questions could have opened up the conversation and helped you discover why Niamh was late for lunch.

Our Take

The ladder of inference outlines the sequence of mental steps we all go through multiple times daily. To get the most from this tool, you don’t need to remember any of the steps from the ladder of inference.

All you need to remember is to make the logic behind your thinking and the reasoning behind the thinking more obvious to others.

So, if you’re thinking of taking action, let people know what action you’re thinking of taking and why. This will improve communication by opening a dialog, helping you discover if your proposed action is indeed the best course to take or whether other facts emerge to make you change your mind.